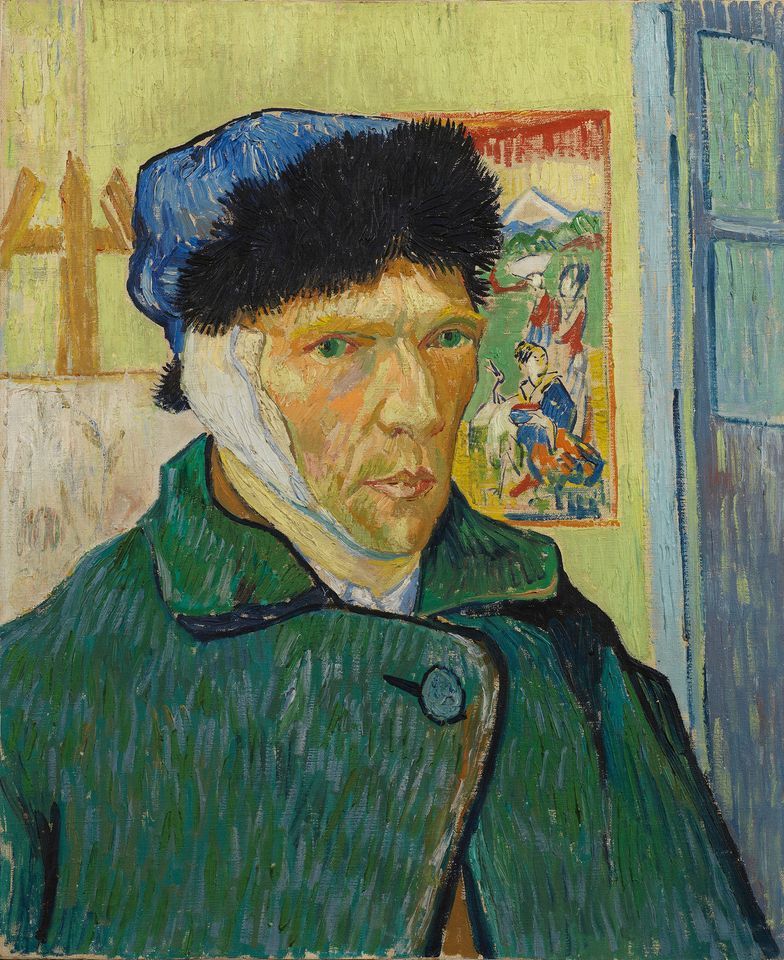

You can’t make it out of middle school art class without learning about a bloody ear. Yet only the most dedicated art historians know the story of Lavinia Fontana.

Compared to the legend of Van Gogh as a tortured artist, Fontana was a true anomaly. Her father, an art teacher, trained her from birth in the fundamentals of painting. She rose to become one of the most commercially successful portrait artists of the Italian Renaissance, a darling of the Bolognese nobility, and is considered Italy’s first female professional artist.

She was so in-demand, in fact, that when she married, her father offered her future painting income in lieu of a dowry. Credit Fontana with another milestone – the first ISA. But Lavinia also lived a stable, happy life. She balanced family with a distinguished career, painting for monarchs and cardinals as she raised eleven children. Sounds like the OG boss woman to me!

And still: Fontana’s story has been lost to the dustbin of history, while every twelve-year-old with a watercolor kit knows about Van Gogh’s razor-wielding rage. When it comes to creative genius, dysfunction and despair are considered the costs of doing business.

The myth of the tortured artist: it’s a convenient crutch. It provides a ready-made excuse for so many of us to shy away from creativity. If creativity comes at the price of sanity, it’s no wonder that many choose to follow safer–and saner–paths. Who wants to dance on that razor’s edge?

Sure, self-mutilation gets headlines. Yet there’s a different mode of creativity. It’s the path to fulfillment by pursuing your best work. It’s the path followed by Lavinia Fontana. It’s the path of craftsmanship.

Craftsmanship is the quality that comes from creating with passion, care, and attention to detail. It is a quality that is honed, refined, and practiced over the course of a career.

“Principles of Great Design: Craftsmanship”, Smashing Magazine

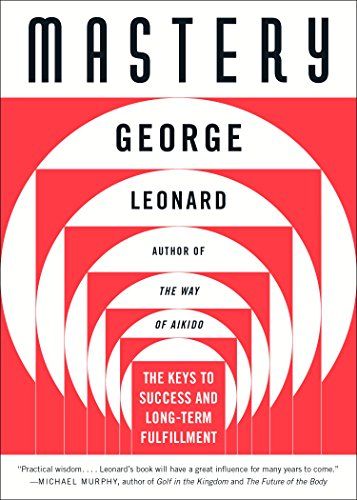

In Mastery, educator George Leonard describes the patient pursuit of continual improvement. On human nature, Leonard writes:

“The human individual is equipped to learn and go on learning prodigiously from birth to death, and this is precisely what sets him or her apart from all other known forms of life.”

The key to mastery, Leonard suggests, is to find reward in the process itself. There are no shortcuts. Obsessing over goals only pushes them further away. When you’re pursuing mastery, get comfortable on the plateau. That’s the plane of practice without improvement–and it can stretch on for ages.

The plateau instills craftsmanship. Through repetition, and accepting the tools you have, you unlock a sustainable and nourishing form of creativity. “The best way to describe your total creative capacity,” Leonard writes, “is to say that for all practical purposes it is infinite.”

The choice is yours: Do you want to burn up your creative energy in one flash-bang reach for greatness, or ration your fuel to light the path of continual creative output?

Consider the two greatest pop songwriters to come out of the sixties: Brian Wilson and Paul McCartney. (Dylan fans: you can check out now.) Wilson’s soaring harmonies and intricate song structures equaled the intensity of his mental illness and self-destruction. He personified the troubled pop-genius.

For many of us, Wilson’s image is frozen in time: mop of hair flopping over dark sunglasses, curling his toes in his living room sandbox while sitting at the piano composing a teenage symphony to God. But sand clogged the gears and rendered the piano permanently out of tune. And the cursed symphony never materialized.

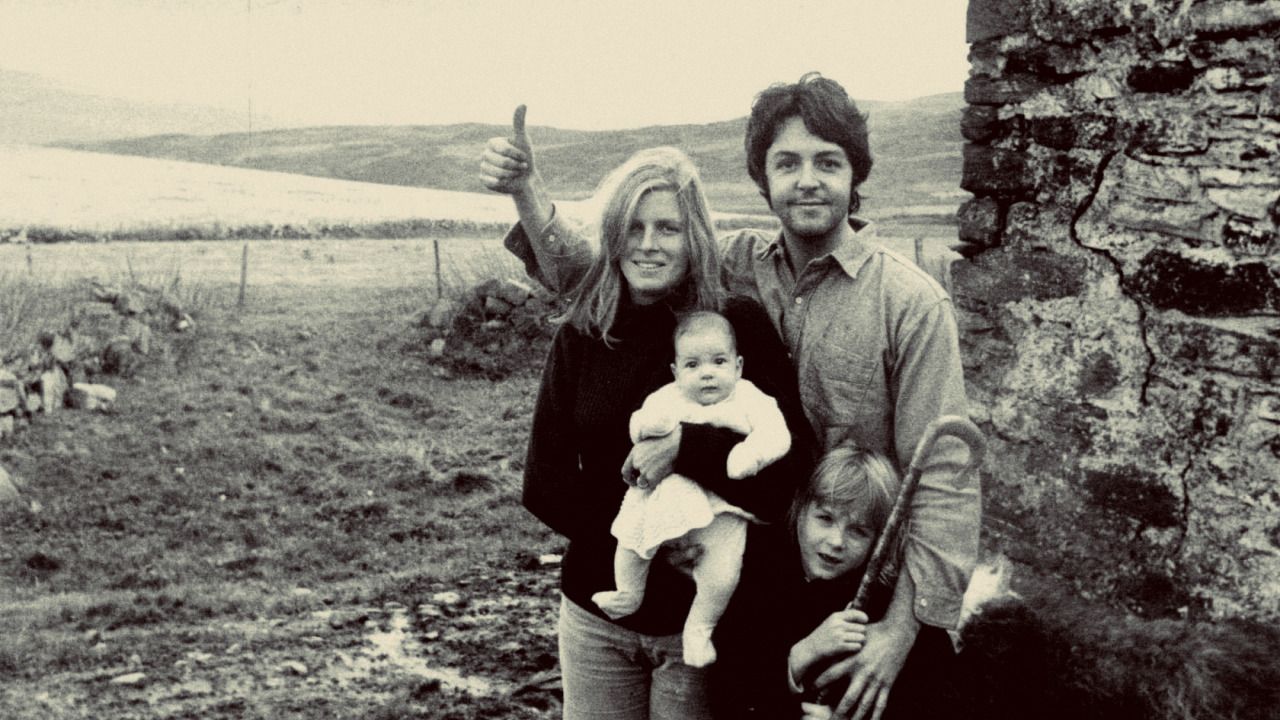

Then there’s Sir Paul. Despite losing his mother at a young age, he grew up happy, free of the trauma associated with most creative geniuses, including his bandmate and foil John Winston Lennon. When the drama and stress of the Beatles reached too high a fever, it wasn’t Yoko who broke up the band. It was Paul.

Now, did he set fires on his way out? Not quite. He retreated with his family to their farm in Scotland, where he reconnected with simple songwriting and played every instrument on McCartney (1970), his first solo album. To be fair: he did sue his former bandmates to cement the breakup. But even a lawsuit reflects a certain civility compared to an intrasquad bare-knuckle fistfight. (See: early Metallica.)

McCartney exudes craftsmanship. He doesn’t mine a haunted past to wring songs from his anguished soul. Rather, he’s dedicated himself to the craft of songwriting. As the son of a former jazz singer, he absorbed musical styles and structures. Driven by insecurity and a desire to be liked, he channeled his friendly rivalry with Lennon into a lifelong dedication to crafting the perfect pop song. He’s still chasing it today, and in doing so, has achieved true genius.

These days, creativity is within reach for all of us. Training, tools, and communities proliferate on the web. We can all try on the life of a creator, if we choose. But the web’s social dynamics push us to achieve more, to reach for higher goals, and to look for quick fixes and growth hacks. Slow, steady growth through small, sequential improvements isn’t sexy. But it works.

So … next time you’re sitting down to work on your side hustle, suspend your need for external validation. Focus on the craft itself. Perform the tasks at hand to the best of your ability. Take pleasure in the process. Know that genius is not an end state, but a spirit to be found through losing yourself in the work. And that’s how true breakthroughs happen.

“Perhaps we'll never know how far the path can go, how much a human being can truly achieve,” Leonard suggests, “until we realize that the ultimate reward is not a gold medal but the path itself.”